Rajkumar Thing, a six-year-old boy from Phulbari in Marin Rural Municipality, Ward no. 4, Sindhuli, is playing near his house. As soon as Kana Thing from Deurali, a neighboring village, meets him, he proposes to take Rajkumar to study at a monastery in India. Luring the innocent child, he promises, "If you go to study at a monastery in India, you will become a great Lama, earn a lot of money, and get free food, accommodation, and education."

Rajkumar, at a playful age, is thrilled by the proposal to go far away from home.

Kana, a 28-year-old man, had arrived in Phulbari on the first week of Jestha, 2076 (May, 2019) searching for boys of Rajkumar's age to take them to a monastery to become monks. He followed Rajkumar, whom he had met on the street, all the way to his house.

Kana proposed to Rajkumar's mother, Sunimaya, to take him to India for education. Sunimaya agreed to send her son as Rajkumar also expressed a desire to go to the monastery and Kana's offer seemed reasonable. Kana had already proposed to Rajkumar's friends, Mingmar Moktan (8) and Man Bahadur Yonjan (12). Mingmar's mother, Anita, and Man Bahadur's mother, Kanchhimaya, also agreed to send their sons. Sunimaya feels comfortable sending her son because he will be going with his friends from the village who play and study together.

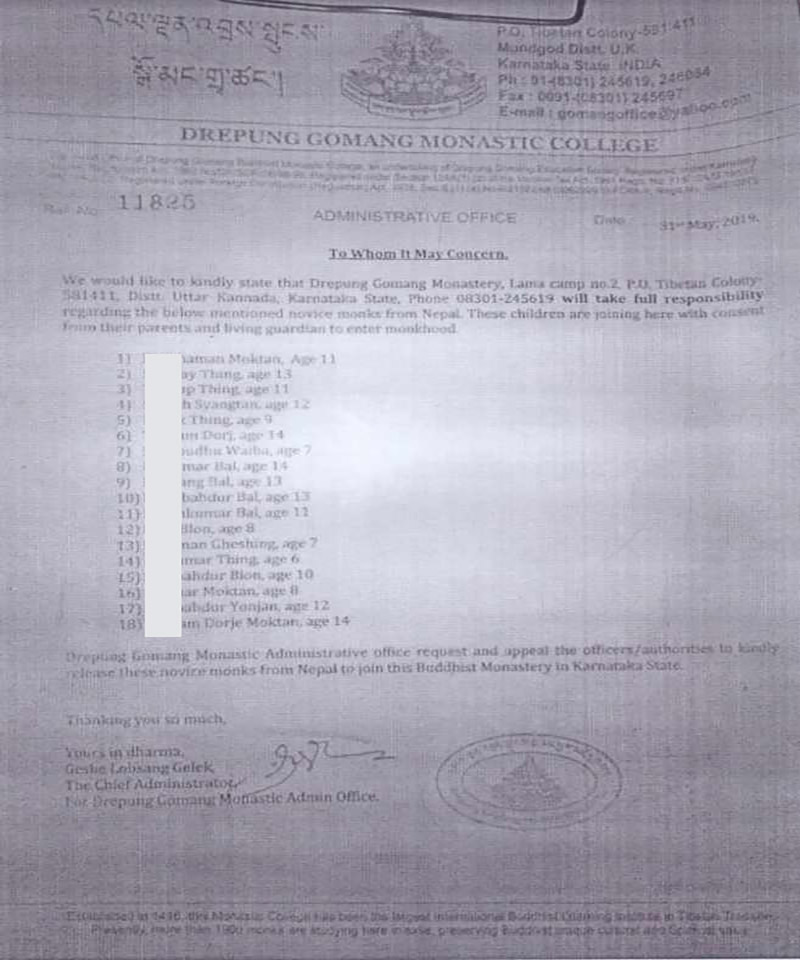

The parents send their sons to India based solely on the promise of being taken to a monastery in India, without any knowledge of the location, purpose, method or duration of their stay. In total, 18 boys from Marin, including Rajkumar, Mingmar, and Man Bahadur, were taken to India through the Malangwa border checkpoint in Sarlahi in Jestha, 2076 (June, 2019). Their own parents helped them cross the border. They left their children in the care of Lal Singh Bal, Kalsang Lama and Kana before returning home.

***

Rajkumar, who went to the Drepung Gomang Monastery in Karnataka, South India, with the dream of studying and becoming a great monk, initially enjoyed himself there. However, as days passed, he wanted to return home. When he spoke to his mother through someone from the monastery, he expressed his strong desire to come home permanently and asked her to come get him soon.

His parents, who had no idea where to go or how to get him when they sent him to study, were now in a dilemma. Their son, who they had expected would return only after completing his education, was now insisting on coming back midway. So, they asked the people at the monastery to bring Rajkumar home.

Since Rajkumar refused to stay and was adamant about returning, the people from Drepung Gomang Monastery brought him to a monastery in Kathmandu in the first week of Asar, 2080 (June, 2023). Sunimaya, who had accompanied her son to the border in Sarlahi in 2019, went to Kathmandu herself to bring him back four years later, in 2023. When she had left him earlier, she had cried for a month. It was the same this time around too. The only difference was that the tears she shed earlier were of separation, while now these were tears of reunion.

After learning about Rajkumar's return, we visited his home in Chyane, Marin, Rural Municipality-4, Sindhuli for the second time on Shrawan 27, 2080 (August 12, 2023). Six months prior to this, on Magh 28, 2079 (February 11, 2023), we visited Chyane and Deurali in Kapilakot Rural Municipality, Ward no. 6, for the first time. Back then, we had met some children who had returned from monasteries in India. Our purpose for visiting again was to understand why Rajkumar agreed to go to the monastery, how he was taken to India, what happened there, and why and how he returned.

Braving the monsoon rain and flooded local rivers, we reached there to find Rajkumar playing with his friends, just like he was when Kana met him in 2076 (2019). "We couldn't play like this there," he said, stopping his game to talk to us. "We had to follow strict discipline and rules." When asked about his experiences at the monastery in India, he replied, looking scared. Considering his state, we talked to him in the presence of his parents. Even then, he answered with a downcast gaze and kept fidgeting with his fingers.

Rajkumar, who is now enrolled in grade 4 at Khayarsaal Madhyamik Vidyalaya in the village after returning home, finds a vast difference in teaching methods between here and the monastery. In the monastery, he had to study from 5:30 am till 12:00 midnight. He was required to understand and recite the day's lessons at night. By the time he could go to bed, it would be 1:00 am. If he couldn't complete his classwork properly or made mistakes, he would be beaten.

"The teacher would hit me wherever he could reach," Rajkumar narrated his ordeal. "I have been beaten with sticks and even phone charger cables. Whenever I was beaten, I would cry, thinking about home and my village." He feels that the fear of being beaten always loomed over him whenever he had to present his classwork.

Rajkumar vividly remembers a time when he was severely beaten for accidentally dropping and breaking a cup during a prayer ceremony in the monastery. "My whole body was bruised, it is healing only now," he says.

According to him, the monastery provided food, accommodation, and education. However, any mistake resulted in harsh beatings, which is why many of his friends there also wanted to return home. "I would be exhausted after studying all day, and if I could not complete the classwork at night, I would not be allowed to sleep," says Rajkumar. "I could not take it anymore, so I came home. I have no desire to go back there ever again." When he went to India, he was six years old. Now, he is 10.

Sunimaya, his mother, was initially unaware of the problems her son faced at the monastery. She says that initially, their phone conversations with Rajkumar were limited to answering their questions, and he would not share anything else. The first time they spoke to him after he was sent to the monastery in 2076 (2019) was two months later.

His father, Somraj, says it took time for Rajkumar to adjust to being back with the family and talk openly. "Things are slowly getting better," he says.

We reached out to the Drepung Gomang Monastery and the Delhi Police to ask about the minors, including Rajkumar Thing, being taken to India to study. We have not received any response from them as of June 24, 2024.

According to Sub-section 2 of Section 15 of the Act Relating to Children (2018), every child has the right to free and compulsory basic education and free secondary education in a child-friendly environment, as per the prevailing laws. Similarly, Sub-section 3 states that every child has the right to education through appropriate learning materials and teaching methods according to their specific physical and mental conditions, as per the prevailing laws. Taking Rajkumar to India to make him a monk and the hardships he endured at the monastery clearly demonstrate a violation of these rights and an injustice done to him, according to child rights activist Milan Dharel.

Neglect of the authorities

During the scorching heat of Jestha (May), Rajkumar said goodbye to his mother. He along with 18 other boys crossed into India with Lal Singh Bal, Kalsang Lama and Kana. After spending three days in Delhi, they boarded a train to Karnataka. At the Nizamuddin Railway Station in Delhi, the sight of 18 children without guardians on their way to Karnataka alarmed the Delhi Police, who took them into custody. Upon learning that the children were Nepali, the police suspected smuglling and immediately informed the Nepali Embassy in Delhi. Coincidentally, the then Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal ‘Prachanda’ was on a visit to India at that time. Busy with welcoming the prime minister, the embassy officials sent a Nepali organization called ‘Afanta Nepal’ (KIN) to check on the condition of the children apprehended at the railway station.

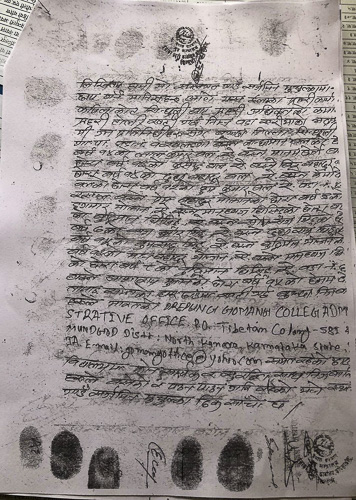

According to Navin Joshi, the then rescue officer at Afant Nepal who reached the police station, it was confirmed that the children were brought through illegal means. However, instead of sending them home, they were allowed to proceed to their destination. Documents were requested from the Karnataka monastery to release the children from police custody. These documents mentioned that the children were being taken to become novice monks. Joshi further states that the people accompanying the children had nothing but birth certificates.

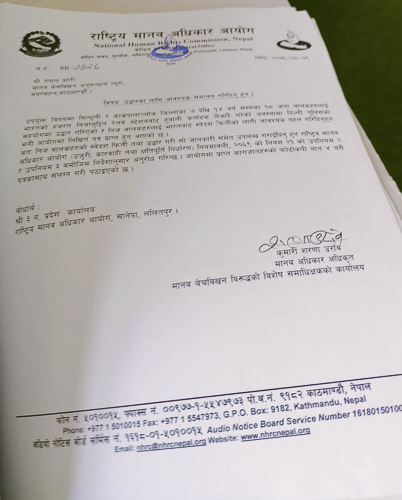

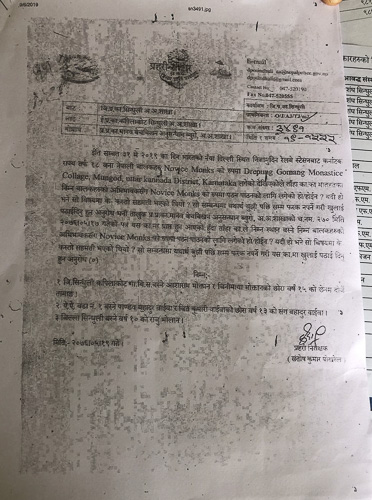

Even though the children were allowed to go to the monastery, Joshi wrote letters to the Human Trafficking Investigation Bureau, the Child Rights Council, and the Human Rights Commission, urging them to take immediate action to rescue the children and return them to Nepal due to the risk of trafficking.

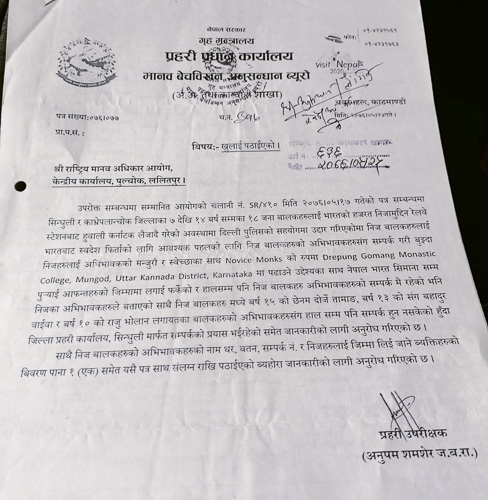

Based on this, the Human Rights Commission also wrote a letter on Asar 9, 2076 (June 24, 2019), requesting the Human Trafficking Investigation Bureau to rescue the children, return them to Nepal, and provide information on the matter. In response, the Human Trafficking Investigation Bureau's letter stated, "Sent with parental consent and in touch with family."

The letter mentioned that contact could not be established with the parents of three of the 18 children: Chhenmong Dorje Tamang, Raju Bholan and Sang Bahadur Waiba. There were meetings, discussions and debates between government and non-government agencies regarding whether or not to repatriate the children who were taken to the monastery illegally without completing the process.

The discussions also raised concerns about the children's rights, well-being and protection. However, investigating the situation of the children sent there did not fall under anyone's responsibility. Anupam Rana, the then Superintendent of Police at the Human Trafficking Investigation Bureau, states, "In the end, the case was closed with a light comment saying they were sent to study."

Somraj Thing, Rajkumar's father, says he only found out about the illegal method used to take his son after the police stopped him in Delhi. According to him, the Kapilakot Area Police Office in Marin called them and asked them to sign documents stating they could contact their son by phone and that he was safe.

The documents we found at the Kapilakot Area Police Office on Asar 27, 2080 (July 12, 2023) confirm this. Records show that the Human Trafficking Investigation Bureau wrote to the Sindhuli District Police Office In Bhadra of 2076 (mid-August to mid-September, 2019), who then forwarded it to the Kapilakot Area Police Office.

According to records from the then Kapilakot Police Office, a local investigation report was created in the presence of the then Ward Chairmen, Kursang Lama (Ward 6) and Dhan Bahadur Syangtan (Ward 4) of Marin Rural Municipality. This report stated that the children were ‘safe and studying’, and the parents were made to sign and stamp it. However, Kursang Lama, the then Ward Chairman of Ward 6, was himself involved in collecting children from the village and sending them to the monastery in India. It appears the police created this report solely based on what the parents were told, without contacting the monastery or verifying the children's well-being.

Article 3 of the Palermo Protocol defines such movement as falling within the definition of trafficking. The article defines trafficking as the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of persons, by means of threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability, or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits in exchange for a person's consent to having control exercised over that person. Based on this definition, it can be argued that these 18 children were victims of trafficking and smuggling. However, the authorities, including the Human Trafficking Investigation Bureau, normalized the movement of these children.

Binod Sharma, Superintendent of Police at the Sindhuli District Police Office, acknowledges the mistake. "The police should not have done that,” he says. “How did such a mistake happen back then?" However, he claims he does not have any information about the incident as he recently joined the office.

***

Who benefits from smuggling children?

There is no exact data on the number of children from Marin who have been sent to monasteries in India. Kajiman Thing, coordinator of the Tamang Ghilin organization in Marin-4, estimates that the number could be between 50 and 60. He says that poor parents send their children hoping for a better life, but emphasizes that separating young children from their families in the name of religion and cultural preservation is worriying. Thing fears that being raised far from family and their country could lead to a loss of language, culture and identity.

"Parents assume their children are well cared for but they lack information about the environment, treatment or educational quality at the monasteries," Thing says.

There have not been any studies on the conditions within these monasteries. Neither the parents nor the people taking the children seem to consider the children's interests or psychology, often using the guise of traditional religious and cultural preservation. This has a negative impact on the children's mental, social and emotional development. Thupten Tamang, a Buddhist philosophy scholar, observes that children brought to monasteries at a young age tend to develop problems like being socially distant, aggressive, and withdrawn.

Thupten has witnessed similar issues in children of his relatives who were sent to study at a young age and other children who studied in monasteries.

Even non-Buddhist children are in monasteries

There are cases where children from non-Buddhist communities are also lured to monasteries in India under the pretense of being educated in Buddhism and preserving the culture.

For example, in Bhadra of 2078 (August 2021), 14 Dalit children from Kunji and nearby areas in Ward 5 of Mustang's Thasang Rural Municipality were rescued from being taken to India on the pretext of becoming Lamas (Buddhist monks). Sunil Dahal, the then Deputy Superintendent of Police at the Kakarvitta Area Police Office, explains that the children were dressed in Lama clothing and were being taken across the border illegally when they were rescued. Police records indicate that smugglers often take children from the East through western borders and vice versa.

Basanta Maharjan, a Buddhist writer and scholar, states that the practice of collecting children from villages and taking them to Indian monasteries is old. According to him, neither the ward offices nor the municipalities have any information about the children taken in this way. "To which monasteries are they being taken? From where are they all being collected? What happens to them after they are taken to the monasteries?" He questions. He further says, "We have no data on how many children are studying in monasteries in India."

Sexual abuse of children in monasteries

There have been cases of violence and sexual abuse against children kept in monasteries and religious institutions in India. According to an online article published in the Daily Tribune in 2018, 15 boys were subjected to beatings and sexual abuse. The police arrested Bhante Shanghpriya Sujoy, a Bangladeshi citizen who headed the ‘Prasanna Jyoti Buddhist School and Meditation Center in Bodh Gaya, Bihar, India. He was accused of beating, sexually abusing and forcing the boys in the monastery to dance naked.

Following his arrest, the International Buddhist Council (IBC) held an emergency meeting and passed a resolution condemning the heinous crime against children in the name of religious education. The resolution also proposed expelling any institution involved in such acts from the Council's membership. It is important to note that many monasteries in India operate without registering with the IBC.

In 2020, Rinpoche Gyana Vajra, President and Head Lama of Shakya Academy in Dehradun, India, was accused of beating 51 Nepali students aged 6 to 17 who requested permission to return home for the Dashain-Tihar holidays. He allegedly beat and confined the students who submitted the request. The incident became public after the victims themselves spoke up. The Nepali Embassy in India and an organization called Help Cross rescued the students and brought them back to Nepal.

Section 64 (1) of the Act Relating to Children (2018) allows the children themselves or concerned individuals to file a complaint with the local government or the local government's judicial committee if a child's rights are violated or if the responsibilities towards the child as outlined in Section 3 are not fulfilled. However, no complaints have been registered regarding these issues.

Why Nepali children?

According to Buddhist writer and scholar Basanta Maharjan, monasteries prefer young children because of the belief that their strong memory allows them to memorize religious texts (sutras) more easily. Memorizing becomes more difficult after a certain age. He explains, "Younger children can grasp things better than older ones. They focus on memorizing until a certain age, after which it becomes harder."

Monasteries with a larger number of students can also use them to impress donors and gain financial or other advantages. Therefore, they strive to have a high number of students. Since there are fewer children studying in monasteries in India, they specifically target Nepali children.

Lal Singh Bal, who takes children to monasteries, claims that the education and facilities are better in Indian monasteries compared to Nepal. He argues that Nepali children are the preferred choice for Indian monasteries because they (especially those from poor and disadvantaged communities) are easier to convince and can be offered fewer amenities.

The plight of returnees

Based on information provided by relatives in Nepal after finding 18 children, including Rajkumar, at the Nizamuddin Railway Station in Delhi, the Human Rights Commission urged the Human Trafficking Investigation Bureau to rescue the children.

The commission's letter provided us with the names and addresses of the children. Following these addresses, on Magh 28, 2079 (February 11, 2023), we first reached Chyane in Ward 4 and Kapilakot Deurali in Ward 6 of Marin Rural Municipality, Sindhuli.

At that time, we learned that Kulsaang Thing (13) and Dhudraj (14) from Kapilakot had returned home after three-and-a-half years. Buddhabahadur Bal, also from Kapilakot, had been back for eight months. They were convinced to leave by their neighbor Lalbahadur Bal, who promised they could earn a lot of money after becoming Lamas (Buddhist monks), while they were still in grade 6 in the village school.

Sushil, Man Bahadur's elder brother, also went to study at the same monastery in Karnataka. Their mother, Kanchhi Maya, says she sent them due to their insistence on studying. According to her memory, she only made phone contact with her older son, Sushil, after a year of him being gone.

For a long time, Kanchhi Maya has been tormented by the memory of her younger son, Man Bahadur, who is seven hundred kilometers away from home. While Sushil has returned, Man Bahadur remains there. She says, "If my son returns, I do not plan to send him back."

Kulsang, who returned home after three-and-a-half years, says he did not know what studying to be a Lama entailed, how the studies would be conducted, or what his future would hold. He came back because the environment and the style of teaching did not suit him. Now 16 years old, Kulsang says, "Going there made me miss my studies here. Now I plan to learn about Lama teachings in the village itself."

He does not know if this knowledge will help him earn a living, but currently, he does not have any other option. Dudhraj, who returned home with him, has started working at a hotel in Kathmandu because he could not find any other choice. He has the responsibility of supporting his family.

Sushil Tamang from Marin Fulbari is preparing to go to Malaysia for foreign employment. He returned because he thought studying to be a Lama in the monastery would take too long. The monastery taught Tibetan, Russian and Nepali students together. However, Nepali students were excluded when it came to making Aadhaar cards.

The person who had taken him, Kana had also taken the 18 boys. Even Kana had been sold to a hotel by a person in the village, according to Lalsingh Bal. While working at the hotel, he met people from the monastery and was then taken there. Since the time he was studying, Kana had been working for the monastery itself. Kanchhi Maya says that Kana not only took her two sons but also used to take other children and teenagers from the village. Kana passed away two years ago.

Starting school again

Supuwang Lama from Kapilakot returned home after studying for five years at a monastery in India. At the age of 13, he and 12 others from the village left to study at a monastery in Siliguri, India. They lacked clear information about the environment and subjects before going. A relative from the same village who was already studying at that monastery took them there.

Supuwang spent five years at the monastery before returning at the age of 18. He had completed grade 5 before leaving for the monastery, but upon returning, he enrolled in grade 8. However, while at the monastery, he forgot his own language. He could not read or write Nepali well enough to take exams.

Most of the 10 who returned with him are now working abroad. Now that educational certificates are required almost everywhere, Supuwang has resumed his studies in the village. At the age of 23, he is taking the SEE (Secondary Education Examination) exams. He says, "I am learning Lama knowledge and skills here in the village, but I regret not being able to complete both paths of education."

In his view, many leave Lama studies incomplete because it is difficult. His younger brother Wangsen, who had been studying at the same monastery for six years, refused to return home.

Supuwang's experience suggests that those who drop out of their studies lack sufficient knowledge. Additionally, the teachings in some Indian monasteries may not align with Nepali religion and culture and may not be practical. The knowledge he received at the monastery itself did not fit well with the village culture either. According to Supuwang, some monasteries do not provide proper education and skills, resulting in monks who have not learned much even after 10 years of study. He advises that before going, one should thoroughly understand the teaching style, culture, and environment of the monastery.

Quoting his fellow monks whom he met at an event for Buddhist monks and Lamas in Bodh Gaya, India, he says, "Some monasteries in Sikkim make students studying to be monks cut grass, milk cows and do cleaning chores."

The Act Relating to Children (2018) guarantees several rights for children, including protection from economic exploitation (Section 7 (6) (a)) and from any act that could cause harm, hinder their education or impede their physical, mental, moral or social development (Section 7 (6) (b)). However, children sent to monasteries seem to be deprived of these rights.

Mental health problems of children separated from families

According to a 2010 article titled ‘Families Not Orphanages’ published in the Better Care Network Working Journal, residential institutions with strict rules limit interaction with family and society. This makes it difficult for children to establish and maintain healthy relationships from childhood to adolescence. The study also found that the mental development of children in residential institutions was 33% lower than that of children who are integrated with their families and communities.

Hasina Shrestha, a clinical child psychologist at the Kanti Children's Hospital, emphasizes the need for a safe and secure environment in residential schools and institutions where children are placed for education. "A bad environment can lead to lifelong psychological problems," she says. According to Shrestha, children in such situations may exhibit symptoms of depression, anxiety, withdrawal, irritability, isolation, fear and even suicidal thoughts. When children are unable to contact their families for extended periods, they may try to run away or self-harm.

There are monasteries for higher education in Nepal

Nepal already has well-equipped monasteries in places like Swayambhu, Chobar, Boudha and Pharping. However, there is a trend of sending underprivileged children aged 6-17 from villages to monasteries in India.

Buddhist writer and scholar Basanta Maharjan argues that there is no need to send children abroad since Nepal already has well-equipped monasteries that offer higher education. "There are language barriers when studying in another country," he says. "They teach in Tibetan, Hindi and the local language. By the time they return to Nepal, they may have forgotten Nepali."

Maharjan adds that even if English is taught, these children might only be able to go to Europe or America. Otherwise, they would be limited to staying within the monastery. He believes it is better to keep children in the country and teach them their own courses. "If we can teach our children our own courses," Maharjan says, "even if they go abroad, they will have knowledge of Nepali religion and culture. They will be able to speak confidently about their own religion and culture."

He argues that by properly raising and educating Lamas, they can then educate followers abroad and promote Nepali religion and culture. Maharjan mentions how foreigners come to Nepal to see and understand Nepali Buddhism and culture. He says, "This can contribute to the promotion of Nepal's historical, religious and cultural tourism."

Maharjan clarifies that he is not against sending children abroad for studies altogether, but that priority should be given to monasteries and schools within Nepal.

There is still demand for children in monasteries

- Lal Singh Bal, the person responsible for taking children to monasteries

No one knows exactly when the practice of taking children from Nepal to monasteries in India began. However, I know that children have been taken from places like Marin in Sindhuli since around 1998.

There are currently 60 children studying at the Drepung Gomang Monastery in Karnataka, India. When the monastery needs more students, they collect children from villages.

Once they cross the border, people associated with the monastery come to pick them up. These monasteries sometimes operate restaurants in various locations in India, and people from those restaurants may also come to collect the children.

In Jestha, 2076 (June 2019), we were caught by the police in Malangwa, Sarlahi, while trying to put 18 children on a train to Delhi. The police released them only after the monastery provided documents. There were no documents or recommendations made when taking them from Nepal. We went without them because the ward office would not provide a recommendation, and the monastery was pressuring us to bring the children. They do not provide anything except food, snacks and travel expenses when taking them from here. They do not provide any documents except a pamphlet with the monastery's contact number.

Previously, when we prepared to send 8 or 9 children, they were caught by the police at the border in Sunauli. After the police released the children who were accompanied by their parents, they were sent again through the Malangwa checkpoint.

The monastery is still asking for children but the ward has not provided a recommendation this time. It is difficult to cross the border without documents, so I have not been able to take them.

Since the ward would not give a recommendation and it became difficult to cross the border, I have not been sending children anymore. They were sent to study Buddhist philosophy, religion and culture. But I do not know much about what happens over there or what kind of education they receive.

(This story was published with support from Humanity United.)

Read our guidelines for Republishing this story here.